A few weeks ago, my wife and I were visiting friends who have been married for over 2 decades. While one never really knows all the ins-and-outs of another couple’s relationship, my wife and I consider these two, who we have known for most of their relationship, to be in a solid partnership, and well-matched. As occasionally happens with companions who spend time together, we just happened to be visiting on a night where things seemed a bit “off” between our friends. We had a nice meal and a few drinks, but there was a mild tension in the air that all of us sensed. After dinner, we settled into some conversation, but it wasn’t long before my wife and I found ourselves the unwitting participants in a spat. We weren’t sure whether it would be best to say our goodbyes and leave them to their argument, or stay and make sure things remained civil. Our discomfort went mostly unnoticed by our hosts, who began to argue in earnest. Eventually we did make a retreat, and no blood was shed that night. In fact, the fight was actually over before we left—and we got to witness a main reason why communication is the glue of relationships.

A few weeks ago, my wife and I were visiting friends who have been married for over 2 decades. While one never really knows all the ins-and-outs of another couple’s relationship, my wife and I consider these two, who we have known for most of their relationship, to be in a solid partnership, and well-matched. As occasionally happens with companions who spend time together, we just happened to be visiting on a night where things seemed a bit “off” between our friends. We had a nice meal and a few drinks, but there was a mild tension in the air that all of us sensed. After dinner, we settled into some conversation, but it wasn’t long before my wife and I found ourselves the unwitting participants in a spat. We weren’t sure whether it would be best to say our goodbyes and leave them to their argument, or stay and make sure things remained civil. Our discomfort went mostly unnoticed by our hosts, who began to argue in earnest. Eventually we did make a retreat, and no blood was shed that night. In fact, the fight was actually over before we left—and we got to witness a main reason why communication is the glue of relationships.This is true no matter what species we are communicating with.

No worthwhile relationship in which humans engage—friends, lovers, spouses, parent/child, boss/employee, teacher/student—exists without bumps and problems. People who have been together for long periods of time have made their partnerships work not because of an absence of problems, but because of an understanding of how to solve them. They stay together not because everything is hunky-dory all the time, but because when problems arise, they willingly deal with them, and find solutions. Just like dogs who are engaged in problem solving become more adept at it with practice, humans who refuse to shrink from their problems, and instead do the uncomfortable work of fixing (or at least exposing them), tend to have deeper, more lasting relationships.

A dog trainer I highly respect said the following once (I’m paraphrasing): “Look, I get the allure of ‘all positive’ training. I wish I could train a dog without using anything but praise and treats and play. That would be lovely! But I cannot—because the dog isn’t getting all the information he needs to be successful, and I know it. I am not setting him up to succeed if I am purposefully leaving out the uncomfortable bits.”

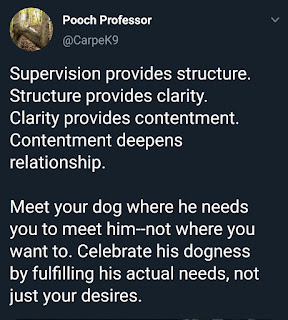

All relationships have stumbling blocks and problems and stressors, but the way to keep the relationship humming is not to avoid the problems or pretend they do not exist, but to address them, break them down, and scatter them out in finer granules so that they may dissipate more easily. Clarity fixes so many issues. No relationship worthy of having can exist in a communication vacuum. Just as dogs require clarity to succeed, our relationships do, too.

Humans and dogs want to avoid conflict, but it’s not always possible. So we need to figure out ways to meet it head on and not shrink from it. Good dog trainers study and practice how to provide negative information in ways that will not scare the dog or cause him to give up completely. We can figure out how to accomplish this with the humans we care about, too.

Every partnership has its stress points. These can vary over time, as we age and grow, or they can burrow in and remain constant, regardless of how the outside world changes around them. Some of us are so attached to our triggers that we just carry them from relationship to relationship like an old piece of luggage we can’t bear to give away.

Dogs engage in natural behaviors that we find unacceptable. In most of these cases, we can train alternative behaviors, or we can stop the dog from engaging in natural behaviors. The main reason to do the latter is for the dog's safety, or the safety of the humans around the dog. For example: resource guarding is a completely natural behavior to most dogs. It is normal for them to be selfish with resources, and sometimes, they feel the need to lash out at humans or other pets if they feel like those resources are being misappropriated. But they don't understand that their "protection" is often misplaced, and that it is rarely needed. They don't understand naturally that those resources aren't really theirs to begin with, either. (A balanced approach to training can alleviate this problem, and it needs to be alleviated because it gets people, especially children, seriously injured. Dogs lose their lives over it, too. It's serious, it rarely gets better without intervention, and it poses a danger. It must be addressed.) Furthermore, resource guarding creates stress for the dog--stress that can be avoided.

Dogs also have milder natural behaviors that "work" fine for them and are not unsafe, but often annoy us: excessive licking (of us or themselves); whining, some types of barking, endless noisemaking with their toys, following us everywhere, digging random holes, and needing to take 20 minutes to find the perfect pooping spot (and then another 5 to find the direction to face while doing their business). Often, these behaviors can be ignored. If these behaviors annoy us sufficiently, we will look for ways to eradicate them safely and humanely. If we are successful, both the human(s) and the dog win.

If we are not successful, we must learn to live with these behaviors.

Similarly, there are always going to be “tics and fidgets” that irk you about your partners and friends. These are actions that your partner does that serve him or her in some way (meaning: they are not a problem to that person), but only serve to annoy you. Some of these are best ignored. If they are not dangerous or damaging to the relationship, you are probably going to be less frustrated by them if you just let them go. If you can’t do this, then the problem must be squarely owned and you must find a way to bring it up and air your frustrations. You may be successful doing so (e.g., your hubby or friend acknowledges that his nail biting habit could be seen as unhygienic, and you’d rather not witness it, so he changes his behavior to not do it in front of you), which will bring you peace, and the relationship thrives.

Sometimes, though, you will not be successful in changing the other person’s behavior. Then what? Can you ignore it? What will the end result be if you cannot? Will things eventually come to a head and boil over? This might actually be a good thing that will help you in the end. Airing grievances and exposing them to light does a couple of things. It communicates to the other person that someone is unhappy with his behavior, which allows him or her to make changes (“when we know better, we can do better”). It also can serve to put things in a different perspective for both parties, and this can help diminish some hurt feelings because when we fixate on problems, they grow in importance in our minds. Once we voice them, and especially if the other person acknowledges that we are frustrated, the problems lose some heft. This is what happened with our friends after dinner.

In my relationship with my dog, I cannot expect that it will be “all positive.” I need to be able to give my dog feedback, and some of that will be about things he does that I do not like. There is nothing wrong with doing this, even if the dog experiences some temporary discomfort, even stress, while receiving the information—especially if it is a dangerous or potentially dangerous behavior, and he is given instructions on how to make it disappear and not return in the future. The dog cannot understand how to behave unless he has experienced some negative consequences to his actions and been given appropriate ways to deal with those bumps.

It doesn’t seem rational, then, when we are talking about people, to avoid having uncomfortable conversations, to kick the problematic can down the road forever, if we can solve them by rolling up our sleeves, bracing for discomfort, and pushing through it--kindly and fairly.

(Now, sometimes the relationship is just not worth it, and you may make the decision to cut and run instead of buckling down. I’m not talking about those types of relationships, or toxic ones. For those, you must take care of yourself first.)

If you feel unequipped for how to do this uncomfortable work in a valuable relationship, or know that the other party may be unable to do the work (or even hear about it), I recommend professional help. Often, we are so close to our problems that we cannot see them clearly, and a professional is not as emotionally attached as we are. (You should feel no more ashamed of seeking professional help in dealing with relationship problems than you would seeking professional help in dealing with an appliance that ceased to run correctly, or seeking a pro to teach you how to play better tennis, ballroom dance, or help you train your dog. Having an unbiased observer can, in and of itself, help immensely in many ways--and a therapist or counselor is more than just an unbiased observer.)

Before my wife and I were about to leave, our friends had a breakthrough. They were able to have it because they didn’t shy away from the discomfort. They both listened. They acknowledged fault. And they acknowledged gratitude, too, which is a very necessary part of ending an argument. As it turns out, there were misunderstandings on both ends. Clarity prevailed, though. The specks of what remained of their argument, exposed to the air, simply blew away.

No comments:

Post a Comment

All comments are moderated. Trolls will be eaten by billygoats on sight.